Simulations!

Simulations!

Computers can be programmed to simulate aspects of physical and cultural reality. Physical reality seems pretty obvious to us, because we’ve been working with it since before birth, but as a system it’s pretty challenging. The universe as an operating system has a difficult-to-understand kernel of subatomic interactions, and you have to consider trillions of edge cases. So it’s always interesting to see how well computers do at simulating reality.

And people simulate all kinds of things. The end of the world, for example. There’s long been a connection between computing and explosions—some of the earliest computers were used for computing ballistic trajectories—and there’s a rich history of nuclear bomb simulation, because it’s always cheaper and more efficient to blow up a nuclear bomb digitally than in a real human city.

It’s important to simulate bad things. Fast Company went and visited the National Infrastructure Simulation and Analysis Center, where they “model cyberattacks, global pandemics, and megastorms.” The upshot is that yep, they expect disasters:

This spring, Sandia’s resiliency arm finished an analysis for Norfolk, Virginia, looking at how extreme flooding could affect the city (and its naval bases) based on NISAC work. The project produced a framework called the Urban Resilience Analysis Process that other cities around the world could use to simulate disasters and predict how they will affect everything from electricity outages to economic impact. “City planners don’t have time to learn the sophisticated mathematical models in the tool,” said Eric Vugrin, a manager of the program, in a news release. Sandia wants to give those tools to cities to use on their own.

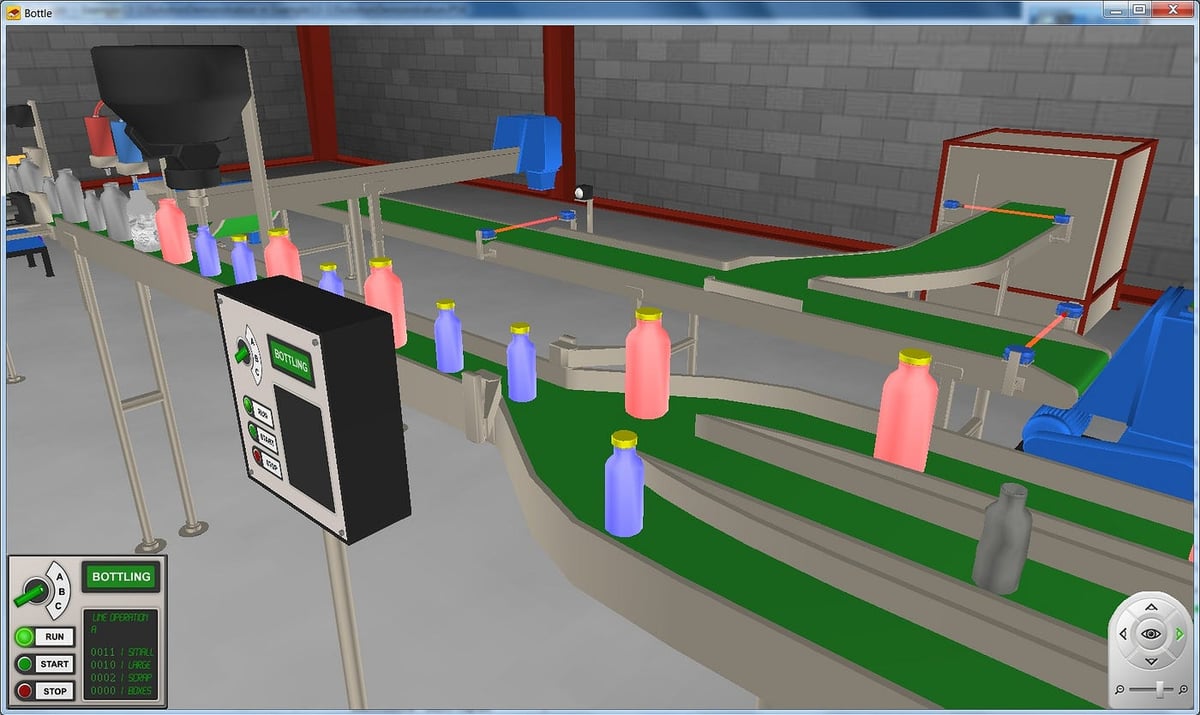

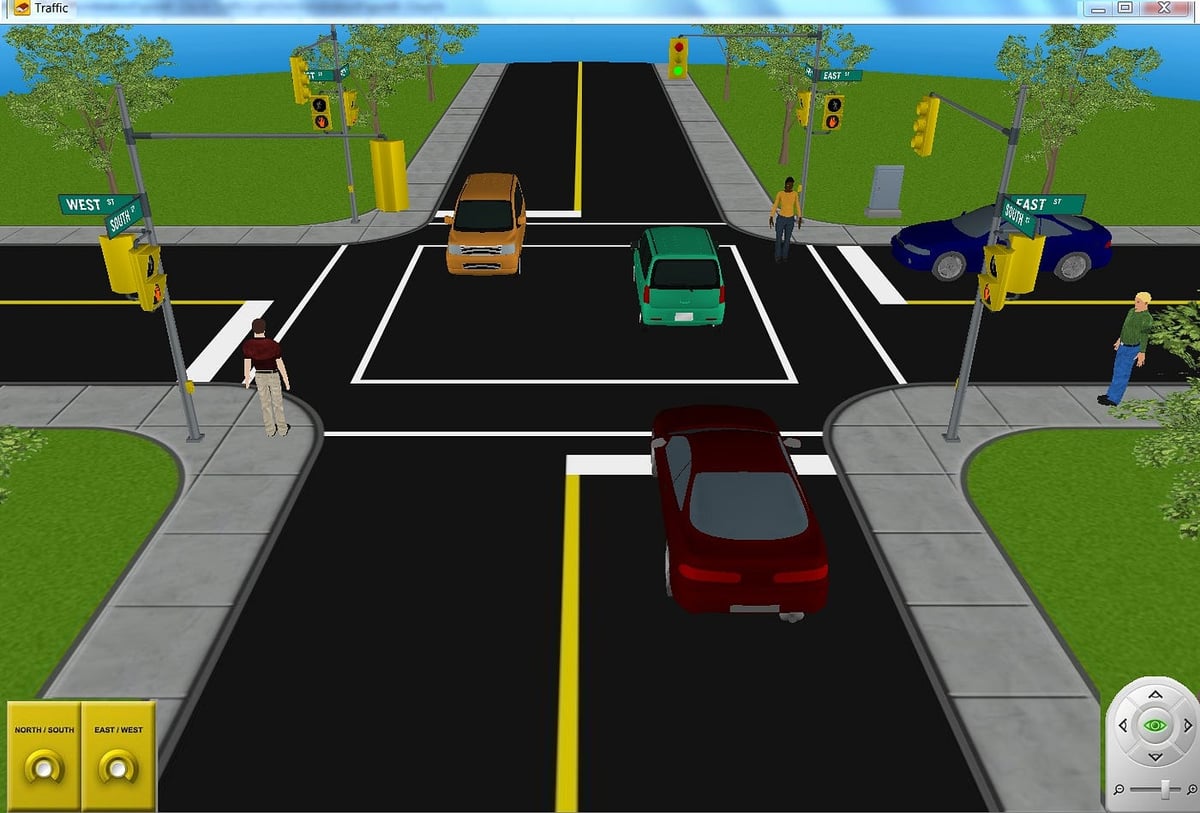

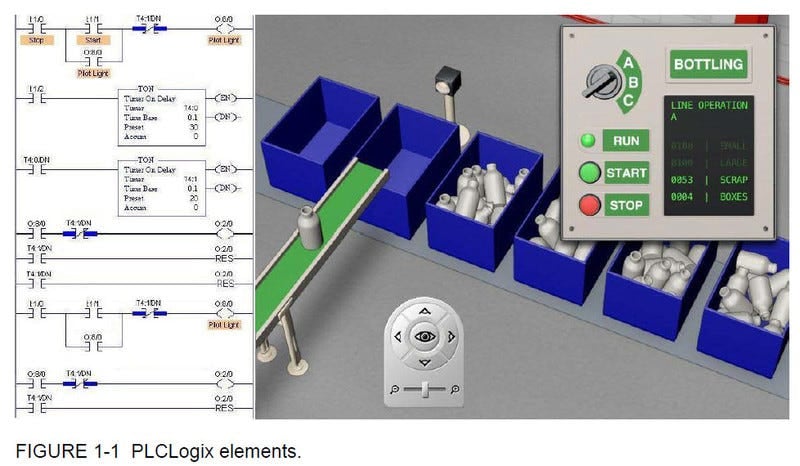

But it’s also useful to simulate nice, normal things. For example there’s a piece of software called PLCLogix, which lets you simulate the sorts of things you do with a Logix 5000 PLC—a sort of computer used to control industrial processes. The world of PLCLogix is filled with weird screenshots of very boring things, like this simulation of an intersection where the Logix 5000 controls the traffic lights:

Or this automated bottling sorter:

Which looks both kind of dry but also, weirdly, fun. And there have been tons of games—it’s a whole category. SimCity is a huge franchise, and Cities: Skylines is a new contender in the city-sim genre that I personally would love to play except it turns my Macintosh laptop into a tiny brick oven. But there lurks inside each of us a secret Robert Moses yearning for urban control, it seems. Take for example a person who made the densest possible SimCity,

. But also: SimWalk! Or SuMO! Or…SimAnt!Another major category of simulation is economics. Early days, there was MONIAC, Monetary National Income Analogue Computer, created in 1949. It’s, well, it’s a series of tubes—a means of modeling the economy using fluids. As Wikipedia explains:

To increase spending on health care a tap could be opened to drain water from the treasury to the tank which represented health spending. Water then ran further down the model to other tanks, representing other interactions in the economy. Water could be pumped back to the treasury from some of the tanks to represent taxation.

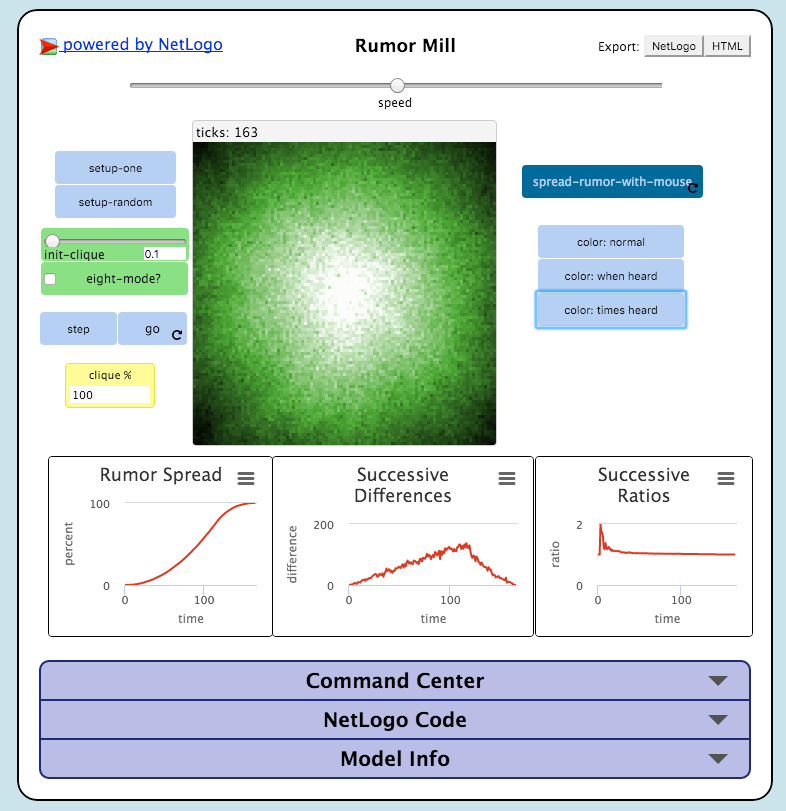

If you’re interested in making your own simulations of things like bee colony behavior or zombie infestations, the go-to tool is NetLogo. It’s been around forever, and it keeps expanding and growing. Out of the box it includes a simulation of how rumors spread; that looks like this:

You can move the sliders and change the code, and model your own rumor mill. It’s amazing how many aspects of human behavior can be modeled as little pixels bumping up against each other, millions of times per minute.