Who Made That: Web Page

A Web page is a machine constructed to profit from attention, and the company that has given the most attention to attention is BuzzFeed.com. It not only optimizes its technology, graphic design and content to attract and sustain the interest of readers — everybody does that — but it also constantly studies their actions and turns this data into the blueprint for its own construction.

How does this happen?

A visit to BuzzFeed.com loads a Web page — words, images, links — in about five seconds. The first tenth of a second sets the stage: your computer identifies itself and requests the BuzzFeed home page. The source code of BuzzFeed’s home page fluctuates, but on one recent afternoon was 9,558 lines of text, as long as a mystery novel. Your browser teases this lump apart and finds that it is made of many things: headlines, links, special instructions in code, style-sheet instructions that lay out the page and pointers to many more files as well.

In short order, your browser creates an instance of what’s known as the Document Object Model, the DOM, pronounced like the Champagne. This DOM is a lively abstraction. One moment it might look like a tree, with paragraphs for branches and words for leaves. Click your mouse and a bit of code runs (the DOM waits always, listens always), and you have turned all the text red or you loaded a video.

All of this behavior is standardized, and there are many standards — long, exhaustive documents that you can download and read — that define the Web. They are necessary because the Web is so many things: text, code, video, audio, interaction, fonts. And, importantly, there’s you, with your clicking and tapping and, in the last few years, your sharing. This is why BuzzFeed is a growing business with 250 people — because you like to share things on social networks. You come to its home page and look for things to share.

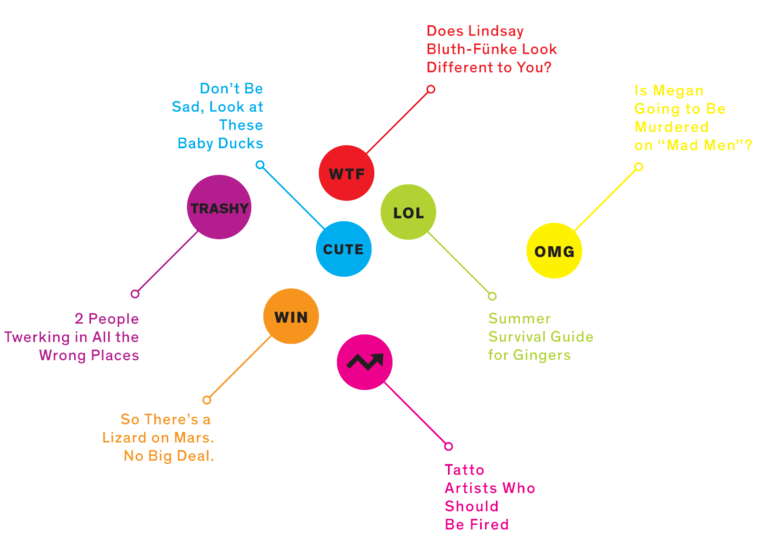

But not yet, for not even a second has passed, and your browser is hungry for more files. It needs images, for example, and many of them, whether small yellow badges that read “omg” or the thumbnail photos that sidle up next to the article and advertisement headlines, each one hoping to draw your eye and get you to click.

The content of BuzzFeed is made the traditional way — by writers and editors. But what distinguishes its approach are the 10 product people who constantly monitor the flows of information between users and systems. Product people want you to touch the site, to do things, the right things. They choose how big images should be and what should happen when you scroll to the bottom of the home page (more articles load). How can all of the parts of the Web page work together to create an experience? An experience that can be experienced over and over by individual users, billions of times collectively?

It takes a lot of cooperation. One of the product people, known as the product lead for editorial tools, works on ways to streamline the content-management system so that ideas can move ever more rapidly from an editor’s brain to pixels on a screen. Another product person, the director of growth, thinks about how to modify the Web site so that, among other things, more people will share more items with social networks like Twitter or Facebook. To get more people to share, you need to know what things are most desirable to share. Sometimes this means that one visitor will see a slightly different version of the Web page than another. One group of users (A) sees one feature; another group (B) sees another. This is known as A/B testing. When a feature gets more clicks, that feature is released to the world.

By the time the second second of your BuzzFeed experience has passed, more than 100 files have come over, and the bulk of the page is there, the parts that you read. What comes over next is a wide variety of trackers, tiny images linked to external services that study what the user is doing. The trackers make it possible to understand how users behave when they are on BuzzFeed.com and also when they visit other Web sites.

Every user action has many possible reactions, many of them occurring in silence. Requests go out to a server called “pixel.adsafeprotected.com” and “amch.questionmarket.com.” You can see the data that is being sent to those sites. One bit reads: “997634-KOxrN-Xqz9_991746” and goes on in that vein for another page. There are other calls made to services like Facebook and Twitter, so that the little widgets that make it easy to share things will be added to the articles. Every one of these calls tells Facebook and Twitter a little more about you, about what you’re reading and what you are like.

At a Web company there is code everywhere. On Web servers, where special programs run and assemble the Web pages — pages that in turn contain more code, which runs in the browser and builds the DOM. Code that you control and code that comes from other places and modifies your code. There is code to make code, code to test code, code in many computer languages. As a result, the engineers and product people try to do small things, make sure they work, then release them. Big things are dangerous. “Scope creep” is a killer.

This hot soup of technologies is a gigantic, automated collaboration. And it moves forward — never the same page twice — guided partly by the desires and will of the people who run Web companies but just as much from the findings of analytics, from the research into user behavior and the upshot of all that A/B testing, which invariably leads to yet more A/B tests. The ultimate answer to “who made that Web page” is: You made that, with your browser, in five seconds, downloading around 260 files. By your behavior, by your preferences, often expressed indirectly, by your laughter at pictures of perplexed animals and your subsequent sharing of those images on Facebook, Twitter or Pinterest, by clicking on an advertisement (or better, sharing it to a social network) you told BuzzFeed, in your capacity as a human represented by a number, a cookie or a username, who you are and what you like to see. And not just BuzzFeed but its partners with their trackers, and the social networks whose widgets are embedded into its page. Tens of millions of you, working together, armed with your curiosity and your Web browsers and increasingly fast network connections. And sharing always, forever sharing.